Biological Contributors to Depression

Depression is not a respecter of persons; it impacts people of all different backgrounds and in all kinds of circumstances. However, there are some biological contributors to depression. It is a complex issue, with many contributing factors. This video examines a few of the biological contributors which, when addressed properly, can reduce the risk of suffering from depression.

In our earlier video entitled, "The Underrated Modern Plague", we showed the terrible impact depression in western societies are having, as the condition in increasing, seemingly with reason.

Depression is not a respecter of persons or their station in life. Some feel their depression is caused by poverty, yet the recent tragic case of Robin Williams, a wealthy celebrity who became its victim, proves otherwise. Success in life also is not a defence. Sir Winston Churchill—nobly born, well-educated, Nobel Prize-winning author, statesman, prime minister, accomplished artist and war hero—suffered repeatedly from what he called "the black dog," that is, depression.

Well, what is depression anyway?

Normally it is defined as a feeling of severe despondency and dejection, which can lead to a sense of despair and loss of motivation.

It is important, as researchers will note, not to include sadness within the definition of depression. We will all feel sad at one time or another due to a circumstance, but a feeling of sadness alone does not constitute mental depression; the latter can have devastating consequences.

Biological Effects:

While experts will admit there are many reasons why a person may fall into bouts of depression, the cause fall into two broad categories "biological" and "non-biological", the latter referring to traumatic events or even lifestyle practice. In this video we will address some biological causes.

According to the Harvard Medical School Journal, there can be numerous causes and contributing factors:

It's often said that depression results from a chemical imbalance, but that figure of speech doesn't capture how complex the disease is. Research suggests that depression doesn't spring from simply having too much or too little of certain brain chemicals. Rather, there are many possible causes of depression, including faulty mood regulation by the brain, genetic vulnerability, stressful life events, medications, and medical problems. It's believed that several of these forces interact to bring on depression10 ("What Causes Depression?," Harvard Medical School, June 24, 2019).

It is a paradox that while activity in certain parts of the brain can affect our mood, our emotions themselves can alter some cerebral functions. Our brain conducts millions of chemical reactions and electrical impulses per second which, along with coordinating our physical functions, also shape our thoughts, moods, memories, skills and ideas, and determine our perceptions, feelings and life experiences. It is an amazingly complex organ whose operation in not yet fully understood.

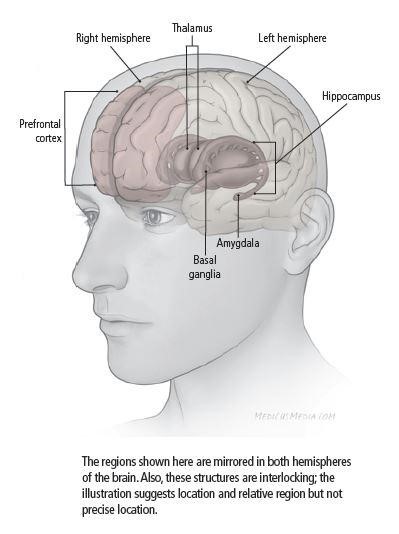

In recent years however, new techniques in imaging have permitted a much better examination of the brain, its circuitry and chemical (hormonal) reactions. We therefore now have a better comprehension of the roles of various structures within the cerebral tissue, including those areas that help regulate mood and may play a significant role in depression: in particular the amygdala, the thalamus and the hippocampus.

Amygdala: A group of structures deep in the brain that's associated with emotions such as anger, pleasure, sorrow, fear. Activity in the amygdala is higher when a person is sad or clinically depressed.Thalamus: The thalamus receives most sensory information and relays it to the appropriate part of the cerebral cortex, which directs high-level functions such as speech, behavioral reactions, movement, thinking, and learning. Some research suggests that bipolar disorder may result from problems in the thalamus.

Hippocampus: The hippocampus has a central role in processing long-term memory and recollection. It is this part of the brain that registers fear. The hippocampus is smaller in some depressed people, and research suggests that ongoing exposure to stress hormones impairs the growth of nerve cells in this part of the brain.

One example of research is a study of 24 women with a history of depression. Their hippocampus was determined to be, on average, 9% to 13% smaller than in women who were not depressed. Stimulating growth of new neurons in the affected region seems to make improvements in their condition12 (Harvard).

Neurons are nerve cells which are uniquely designed to transmit and receive messages, or when appropriate, to block a message. The cell body possesses connectors that interact with other cells consisting of dendrites and axons which control transmission and reception of messages between neurons. The chemicals used in this communication are called neurotransmitters.

Between the connectors of two adjoining cells is a small space called a synapse. To make a message bridge this gap, the cell sends molecular chemicals—the neurotransmitters—into it, that bind with the receptors of the two cells and enable the message to cross. Thus these "activating" neurotransmitters facilitate the communication. On the other hand, a neuron may produce a chemical that prevents the transmission. These are known as "inhibitors." To date six of these essential chemicals have been identified.

One neurotransmitter, acetylcholine, is important for enhancing memory, learning and recall. Another, serotonin, regulates sleep and appetite, but low levels can have serious depressive effects. Dopamine, a hormone which is essential to movement as well as motivation, also helps in the perception of reality; an imbalance in this chemical can result in a distorted sense of reality.

Thus problems can occur when neurons produce too much or too little of an activator or inhibitor for different situations within the limbic system; a depressed mood is one possible result, which can be mild or severe, depending on the chemicals involved.

The medical community is making significant strides in identifying the functions of neurotransmitters and prescribing treatments that can assist a patient to experience improvements in dealing with biological causes of depression.

In addition to problems with neurotransmitter chemicals that can contribute to clinical depression, there are some other possible contributors to the disorder.

One can inherit a genetic predisposition toward some level of depression. Our genes define who and what we are and we depend upon them to make the right proteins when needed. If however a gene turns off at the wrong time or overproduces due to a fault, elements within our body can experience problems, as can our moods.

Our temperament can be a factor. To a considerable extent temperament is an inherited trait, helping to determine how quickly we might get angry, frustrated or excited. This impacts how one handles a sudden crisis, disappointment or rejection. Genetics, combined with our experiences, can shape our approach to life. Our experiences are in many ways a product of the environment we are in (or have put ourselves in) and the actions we decide to take or not to take. Our chosen behaviours can in fact make us more vulnerable to depression, or more able to overcome such negative feelings. Later in the series we will look at ways we can positively address such challenges.

Seeking advice and a diagnosis from skilled medical practitioners can help determine if depression is caused or enhanced by direct biological factors, and a range of treatments may be available.

In our next episode we will be discussion non-biological or behavioral contributors to depression and discussing how these can be managed.